The badge of adulthood, for a literary style, is the nervousness of affect—the compulsion felt via an enthusiastic editor to pee upon a fireplace hydrant that an previous eminence as soon as peed upon with difference. Rebecca West, an unjustly ignored deity of “novelistic” reportage, would have authorized of the vulgarity of this metaphor. Within the 1941 masterpiece “Black Lamb and Grey Falcon,” the place she micturated upon the hearth hydrant of Yugoslavia for 11 hundred gloriously digressive pages, a “lavatory of the old Turkish kind” conjures up a longer rumination on its dim dung hollow.

The Fresh Yorker editor Janet Malcolm, one in all West’s biggest heirs, would by no means have dwelled on such crude ground. However a lot of Malcolm’s preoccupations have been recognizable as makes an attempt to triumph over the debt that she owed her precursor. Prison conflicts—like the only on the center of Malcolm’s “The Journalist and the Murderer”—build for a excellent instance. West, who blended a psychoanalytic aversion to sentimentality with an anthropological interest, impressed a age of writers to render court court cases as a civilized translation of a primordial ceremony. In 1946, her dispatch from Nuremberg started, “Those men who had wanted to kill me and my kind and who had nearly had their wish were to be told whether I and my kind were to kill them and why.” Vengeance may have underwritten a given trial’s stakes, however circumstances themselves have been to be taken in as stylized performances. West handled trial protection as a variant of drama complaint.

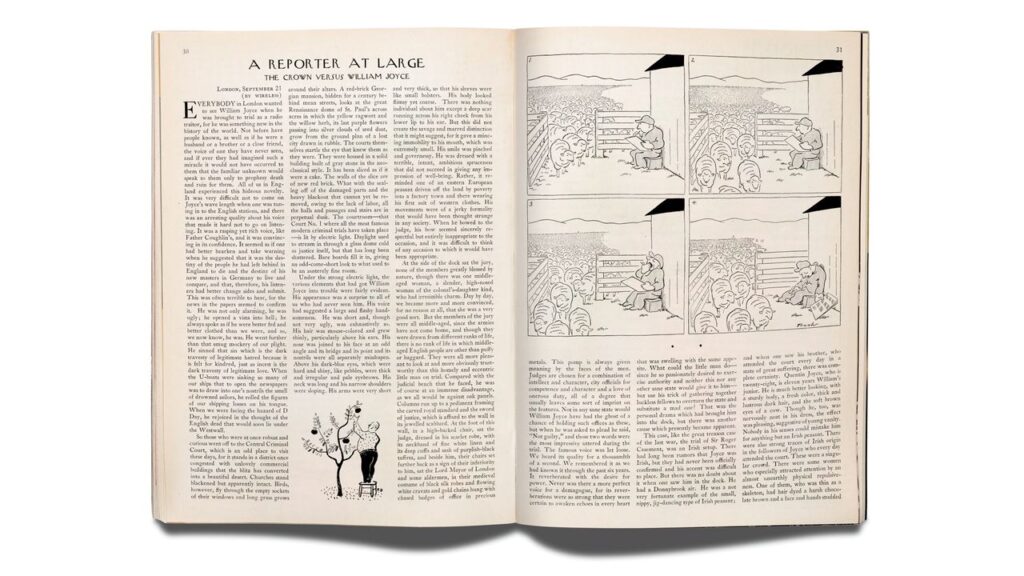

West reserved her maximum operatic respect for tragedies of betrayal—“the dark travesty of legitimate hatred because it is felt for kindred, just as incest is the dark travesty of legitimate love.” A age prior to Nuremberg, West chronicled the prosecution, in London, of William Joyce, alias Lord Haw-Haw. Joyce used to be a second-tier Fascist who had defected to Berlin to provide as a radio broadcaster for the Nazis’ English provider. He used to be notorious in Britain for his bloodthirsty prophecies of German triumph.

The courthouse target market’s vexed dating with Joyce used to be “something new in the history of the world”—a prototype of the parasocial. Joyce’s expression “had suggested a large and flashy handsomeness,” however his look needy the necromancy. “He was short and, though not very ugly, was exhaustively so,” with the glance “of an eastern European peasant driven off the land by poverty into a factory town and there wearing his first suit of western clothes.” (Outdoing Malcolm in her cold dispassion, West used to be cruel with the broke jurors as neatly: “though they were drawn from different ranks of life, there is no rank of life in which middle-aged English people are other than puffy or haggard.”)

What should be West’s really extensive legacy has been decreased to her wit, and he or she used to be hilariously unsparing in her remedy of Joyce as “flimsy yet coarse.” This, West used to be neatly conscious, represented a crystallization of the angle that impressed his latest treason. Joyce’s younger high-society aspirations were brushed aside, and the ache of this trauma fed his populist resentment: “What could the little man do—since he so passionately desired to exercise authority and neither this nor any other sane state would give it to him—but use his trick of gathering together luckless fellows to overturn the state and substitute a mad one?”

Unfavourable via the shrewd status quo, Joyce ingratiated himself with a counter-élite that may dignify his bitterness as political braveness. His myth of condition and function destined him for Berlin, which he believed may just educate England a factor or two about outdated martial valor. In many ways, he prefigured the toadying courtiers of our occasion’s Fresh Proper, who fawn over despots with the similar pick-me worship.

West discovered Joyce virtually underneath contempt. The bureaucratic march towards his conviction used to be nonetheless “more terrible than any other case I have ever seen in which a death sentence was given.” Privately, she wrote, “I am consumed with pity for Joyce because it seems to me that he lived in a true hell.” The deadpan pathos of her record painted this hell as a shared fact. The depression that each created Joyce and attended his execution used to be common: “Nobody in court felt any emotion when he knew that Joyce was going to die.” ♦

Source link